Porcine brucellosis:

an underestimated disease in Sardinia

Overview on brucellosis

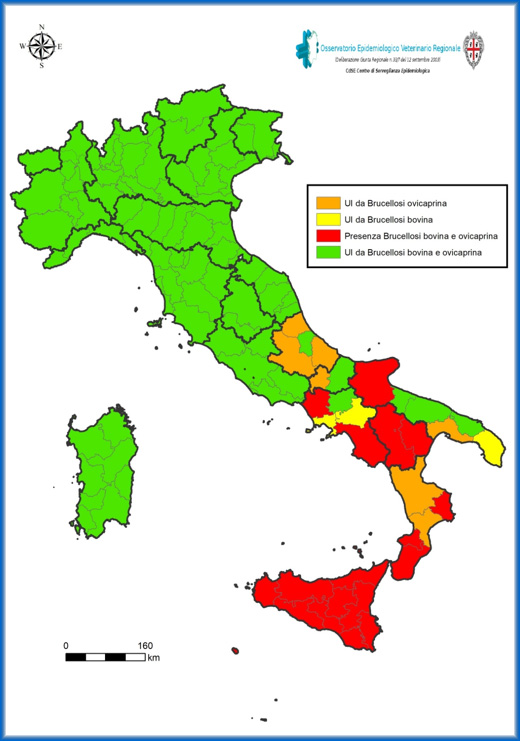

Brucellosis is a globally widespread zoonosis caused by Brucella spp. Currently, America, North Africa and some European countries are the most affected. Australia and New Zealand have achieved eradication after more than 20 years and they are currently in free status, thanks to the application of maintenance programs (Zhang et al., 2018). Japan has also substantially eliminated the disease and currently it applied valid surveillance strategies (Yamamoto et al., 2008). In Germany, eradication of bovine, ovine and caprine brucellosis had been achieved, but in recent years, the disease has reappeared in other animal species (rodents) (Hammerl et al., 2017). On the other hand, in Italy it is still present, especially in the southern regions; Sardinia is one of the Officially Free Regions from bovine and ovine-caprine brucellosis, as shown in Figure 2, which indicates all the Free territories of Italy, as recognized by the Community Decision 2021/385.

Recently, an outbreak of Brucella canis was recorded in a commercial breeding farm located in Marche, involving a very high number of dogs (De Massis et al., 2021).

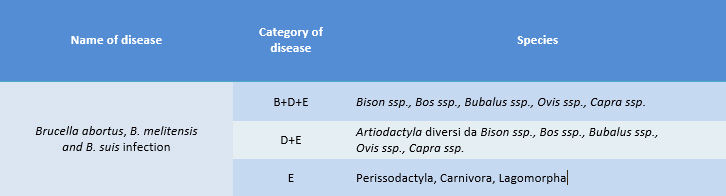

The application of the new legislation on Animal Health, in particular of Regulation 429/2016 and of the Delegated Regulations, the level of attention has also increased on the spread of Brucella suis infections, as showed on Table 1 that referred to Article 2 of Regulation 2018/1881.

Table 1  “Category B disease”: disease that must be controlled in all Member States in order to eradicate it throughout the Union

“Category B disease”: disease that must be controlled in all Member States in order to eradicate it throughout the Union

“Category D disease”: disease for which measures are necessary to prevent its spread due to its entry into the Union or movements between Member States

“Category E disease”: listed disease for which there is a need for surveillance within the Union.

Figure 1. Map of the spread of ovicaprine and bovine brucellosis in the Italian territory

Source: Regional Veterinary Epidemiological Observatory

Brucellosis affects animals and humans and the causative agent is a Gram negative microorganism, facultative intracellular, asporigenous. Within the genus Brucella there are 9 species, B. abortus (biovar 1,2,3,4,5,6,9) (cattle, bovidae and cervidae), B. melitensis (biovar 1,2,3) (sheep and goats), B. suis (biovar 1-5) (pigs, reindeer, wild rodents), B. ovis (ram), B. canis (dogs), B. neotomae (desert rat), B. ceti (marine mammals), B. pinnipedialis (marine mammals), B. microti (common vole).

Brucella abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis are the most important species due to their high pathogenicity.

Brucella suis is the causative agent of porcine brucellosis, a chronic disease that causes major reproductive disorders, such as miscarriages, stillbirths, infertility, orchitis and epididymitis in males. Five different biovars of B. suis have been identified: among these, biovars 1, 2 and 3 are pathogenic for domestic pigs, wild boars, cattle and sheep. European hare (Lepus europaeus) and wild boar have been identified as natural reservoirs of biovar 2 (mainly responsible for porcine brucellosis) (Qing-Long Gong et al., 2021; van Tulden P. et al., 2020). Biovars 1 and 3 are also able to infect humans through direct exposure to secretions from the skin and mucous membranes of infected animals, aerosol particles, consumption of infected foods (raw milk and meat). A high risk of infection is recognized, in particularly, to workers in the sector due to their greater exposure (veterinarians, farmers, slaughterhouse workers) (Spickler Anna Rovid, 2018).

World livestock production attributes to the pig sector, represented by both traditional small-scale production and intensive pig farming, a very important role since pork is the most consumed meat, accounting for more than 36% of meat intake globally. This value has remained constant in recent decades, strengthening the role of this sector in the world industry (Beltran-Alcrudo et al., 2019). Brucellosis is considered one of the main diseases affecting this sector of industry, causing extensive damage to the economy (Qing-Long Gong et al., 2021).

Data on the prevalence of porcine brucellosis in the world are scarce, but it is certain that the conditions and density of intensive farming should be improved. The biosecurity conditions of pigs in small farms should be improved in order to prevent contact with wild boars and thus reduce the possibility of infections between wild and domestic pigs (Qing-Long Gong et al., 2021).

Diagnostic methods such as PCR allow to detect DNA of Brucella in samples. Whenever possible, Brucella spp. is isolated by culturing specimens such as uterine or mammary secretions, aborted fetuses or specific tissues, such as lymph nodes, spleen, male and female reproductive organs. Identification and typing, using specific genomic sequences, can be additional methods for the characterization of the pathogen (OIE, 2018).

Other diagnostic methods are used for the direct diagnosis of Brucella: for example, it is possible to arrive at a presumptive demonstration of the presence of the pathogen in the aborted fetus or vaginal discharge’s material by using a specific staining.

Serological tests (Rose Bengal test, complement fixation, ELISA, fluorescence polarization assay) represent indirect diagnosis: they are screening tests and none of these are specific test for individual animal species. The detection of positive samples in such screening tests should be investigated using a confirmed or complementary test.

Porcine brucellosis in Sardinia

There are few data on the incidence of porcine brucellosis in Sardinia and we cannot assess the real prevalence of Brucella suis. Pilo et al. reported a survey on Brucellosis in farms that have shown reproductive problems and another survey on Brucellosis in wild boar from the hunting campaign (Pilo et al., 2014; Pilo et al., 2015).

The study concerning domestic animals covered the 2007-2010 period, during which the animals belonging to 108 farms were screened. 33% of these farms showed seropositivity to Rose Bengal, Complement Fixation and ELISA tests, and cultural tests showed the presence of a single infectious species, B. suis (Biovar 2 confirmed by the National Reference Centre for Brucellosi - IZSAM "G. Caporale") (Pilo et al., 2014).

As for the wild, in the 2009-2010 hunting campaign, an antibody prevalence of 6.1% was detected, a percentage similar to other regions of Italy (Piedmont and Campania) (Pilo et al., 2015; Bergagna et al. 2009; Montagnaro et al. 2010). This confirms, also with cultural isolations and specific detection by PCR tests in seropositive animals, that wild boars represent the natural reservoirs of B. suis biovar 2, and their contacts with domestic pigs lead to the spread of the pathogen between these two species (Pilo et al., 2014; Pilo et al., 2015; Cvetnic et al., 2009).

In Sardinia, in 2014, a surveillance program for porcine brucellosis was implemented to both domestic and feral pigs. The Plan should have been implemented to farms on the base of the risk level (from level 1 to level 5), instead the farms with animals with evident symptoms were mainly involved. In many cases, samples collected as part of other control activities were subjected to serological screening for brucella.

On the other hand, the number of wild pig samples tested for brucellosis was influenced by various factors, as the hunting pressure in the territory, the presence of other diseases for which the control in wild boars must be carried out (the suitability of the matrices provided to carry out the test could have been a problem) and, a factor of extreme importance, the awareness of the hunters towards health problems.

The Plan also foreseen to study the role of hare as a reservoir of Brucella spp..

The samples were initially subjected to a screening by rapid serum agglutination test (RBT) and subsequently, based on the outcome of this first test, they were subjected to further tests (Complement fixation, ELISA, culture test).

Some critical issues emerged from the implementation of this Plan and they limited a correct evaluation of its effectiveness: one of this critical issue is the absence of data of the disinfection actions of farms located in risk levels 4 and 5.

The analysis of data collected in 2011-2014 allowed us to clarify the importance of porcine brucellosis in both domestic and wild pigs, and the underestimation of this disease and its effects.

The outbreak farms have implemented high biosecurity standards, hence it is unlikely that the entry of the disease was caused/due to contact between farmed and wild pigs; whereas, the spread of the disease is more likely due to the introduction of infected breeding animals (Annual report on multi-annual national control plan 2014).

It was not possible to evaluate the role of the Sardinian hare (Lepus capensis mediterraneus) as a reservoir for Brucella suis, as widely demonstrated in the rest of the European continent (European brown hare), due to the low number of Sardinian hare killed during the hunting exercise and subjected to control.

References

- Beltran-Alcrudo D., Falco J.R., Raizman E., Dietze K. (2019) Transboundary spread of pig diseases: the role of international trade and travel. BMC Vet Res., 15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1800-5

- Bergagna S., Zoppi S., Ferroglio E., Gobetto M., Dondo A., Di Giannatale E., Gennero M.S., Grattarola C. (2009) Epidemiologic survey for Brucella suis biovar 2 in a wild boar (Sus scrofa) population in northwest Italy. J Wildl Dis, 45:1178–1181

- Cvetnic Z., Spicic’ S., Toncic´ J., Majnaric´ D., Benic´ M., Albert D., Thiebaud M., Garin-Bastuji B. (2009). Brucella suis infection in domestic pigs and wild boar in Croatia. Rev Sci Tech, 28:1057–1067

- De Massis F., Sacchini F., Averaimo D., Garofolo G., Lecchini P., Ruocco L., Lomolino R., Santucci U., Sgariglia E., Crotti S., Petrini A., Migliorati G., D'Alterio N., Gavaudan S., Tittarelli M. (2021) First Isolation of Brucella canis from a breeding kennel in Italy. Vet Ital., 13;57:3. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.2497.15848.1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34641664.

- Gong Q-L., Sun Y-H., Yang Y., Zhao B., Wang Q., Li J-M., Ge G-Y., Chen Z-Y., Shi K., Leng X., Zong Y. and Du R. (2021) Global Comprehensive Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Brucella spp. in Swine Based on Publications From 2000 to 2020. Front. Vet. Sci., 8:630960. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.630960

- Hammerl J.A., Ulrich R.G., Imholt C., Scholz H.C., Jacob J., Kratzmann N., et al. (2017). Molecular survey on brucellosis in rodents and shrews - natural reservoirs of novel Brucella species in Germany? Transbound Emerg Dis., 64:663–71. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12425

- Annual report on multi-annual national control plan 2014. Ministero della Salute

- Montagnaro S., Sasso S., De Martino L., Longo M., Iovane V., Ghiurmino G., Pisanelli G., Nava D., Baldi L., Pagnini U. (2010) Prevalence of antibodies to selected viral and bacterial pathogens in wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Campania Region, Italy. J Wildl Dis, 46:316–319

- OIE (2018). Brucellosis (Brucella abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis) (infection with B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis) In OIE Terrestrial Manual Chapter 3.1.4, pp 355-398

- Pilo, C., Tedde, M., Orrù, G., Addis, G., & Liciardi, M. (2014). Brucella suis infection in domestic pigs in Sardinia (Italy). Epidemiology and Infection, 143(10), 2170-2177. doi:10.1017/S0950268814003513

- Pilo C., Addis G., Deidda M., Tedde M.T., and Liciardi M. (2015) A Serosurvey for Brucellosis in Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) in Sardinia, Italy. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 51(4), pp. 885–888. DOI: 10.7589/2014-11-264

- Spickler, Anna Rovid (2018). Brucellosis: Brucella suis. Retrieved from

- Takehisa Yamamoto, Toshiyuki Tsutsui, Akiko Nishiguchi, Sota Kobayashi (2008) Evaluation of surveillance strategies for bovine brucellosis in Japan using a simulation model. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, Volume 86, Issues 1–2, Pages 57-74, ISSN 0167-5877

- van Tulden P., Gonzales J.L., Kroese M., Engelsma M., de Zwart F., Szot D., Bisselink Y., van Setten M., Koene M., Willemsen P., Roest H.J., van der Giessen J. (2020) Monitoring results of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in The Netherlands: analyses of serological results and the first identification of Brucella suis biovar 2. Infect Ecol Epidemiol., 10(1):1794668. doi: 10.1080/20008686.2020.1794668

- Zhang N., Huang D., Wu W., Liu J., Liang F., Zhou B., et al. (2018) Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Prev Vet Med., 160:105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.10.002.

Annamaria Coccollone,

Daniela Mandas,

Manuele Liciardi

Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sardegna “G. Pegreffi'', SCDT di Cagliari