The epizootic haemorrhagic disease, a year after

Introduction

The epizootic haemorrhagic disease (EHD) is a vector bone infectious non-contagious disease, affecting domestic and wild ruminants. The causative agent is the EHD virus (EHDV), classified under the Sedoreoviridae family and Orbivirus genus. It is closely associated with the bluetongue virus (BTV), sharing the same family and genus (Savini et al., 2011).

There are currently 7 known serotypes of EHDV, namely 1,2 and 4-8 (EFSA, 2009).

Some species of the Culicoides genus are implicated in the transmission of EHDV, and the same species are likely responsible for the transmission of BTV. It is possible that the two different diseases, EHDV and BT, may also have the same vector-virus interaction mechanism, ecology, seasonality and vector control (Savini et al., 2011; Quaglia et al., 2023).

The first time the EHDV was described was in 1995 in New Jersey (USA), where an epizootic affected the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Shope et al., 1955). This species shows greater mortality and morbidity, while the infection in bovine is usually asymptomatic/paucisymptomatic (Savini et al., 2011).

Some experimental studies and epidemiological investigations have also reported goats, sheep, various species of cervids, ibex, yak, American bison, but also camelid as susceptible species, with symptoms and anatomopathological findings varying in severity (Avelino de Souza Santos et al., 2023; WOAH, 2019; Spedicato et al., 2023). In white-tailed deer, EHD can cause per-acute symptoms weakness, lack of appetite, sialorrhea, oedema and hyperaemia of the conjunctiva and oral mucous membranes, erosions and ulcers of the muzzle, hard palate and tongue, cercino-coronitis with lameness and detachment of the wall of the claw.

Clinically affected bovines show fever, hyperaemia and erosion of the oral mucosae, sialorrhea, hyperaemia and ulcers of the muzzle, cyanosis and oedema of the tongue, hyperaemia of the conjunctiva and haemorrhagic effusions of the teats. Death is a rare event (Savini et al., 2011; WOAH, 2019).

Furthermore, EHD is also responsible for significant economic losses due to abortion, infertility and decreased of the milk production, as well as increase in veterinarian costs (Savini et al., 2011; Yadin et al., 2008; Kedmi et al., 2010).

Epidemiology

The epizootic haemorrhagic disease is endemic in some North American regions, in Australia and some countries in the Middle East and Africa, but its presence has also been reported in South America and Asia (Jiménez-Cabello et al., 2023)

In September 2021, the viral circulation was confirmed in Tunisia, where outbreaks had already been reported in 2006 (Sghaier et al., 2022). Sghaier and colleagues, thanks to genome sequencing techniques, identified serotype 8 as responsible for the EHD outbreak in 2021.

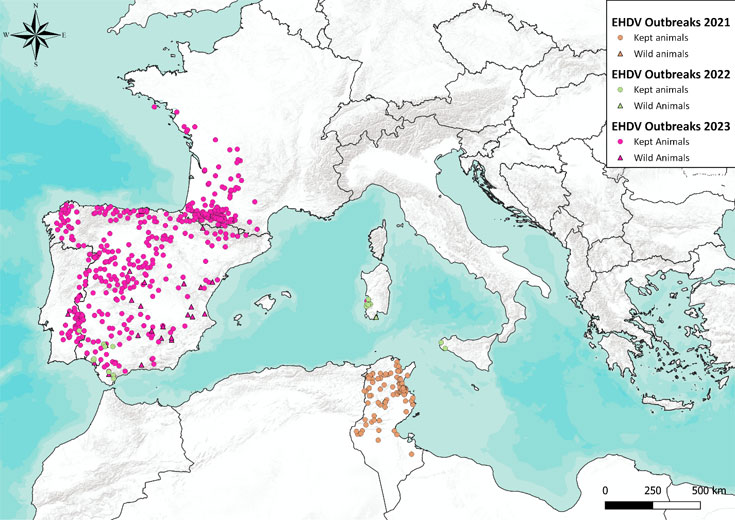

The EHD has also been present in Europe since October 2022 (fig. 1). The disease was suspected for the first time in Italy on a farm in the province of Trapani, Sicily, where 3 cattle showed respiratory distress, erosion of the oral mucosae and muzzle and sialorrhea.

A few days later, on a cattle farm in Arbus, in the province of South Sardinia, in Sardinia region, some animal showed loss of appetite, cyanosis and oedema of the tongue, conjunctivitis and fever, and some animals died. The Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Abruzzo and Molise regions confirmed the positivity to EHDV, and identified the serotype 8 (EHDV-8) as responsible of the infection.

The genotyping of the strain has exhibited almost complete similarity (>99.9%) with the serotype circulating in Tunisia in 2021, EHDV-8 TUN 2021 (Lorusso et al., 2023), corroborate the hypothesis of a north African origin of the virus that most likely arrived with sand storm carrying infected Culicoides.

.

Figure 1. FEHDV outbreaks in Tunisia and Europe, 2021-2023. Sources : WAHIS, ADIS

Moreover, in November 2022, the presence of EHDV-8 was found in Cadiz and Seviglia, in Andalusia, Spain (WAHIS).

The new vector season for the year, from late summer to autumn (WOAH, 2021), has led to a new spread of the disease.

In Spain, the virus was able to “overwintering” and new cases were confirmed from July to October 2023 with the complete involvement of the national territory (ADIS). The Spanish Ministry of Agriculture reported that, in these outbreaks, only bovine showed clinical signs while sheep and goats were asymptomatic. From the beginning of the epidemic to 17 January 2024, in Spain, 278 EHDV outbreaks were confirmed by the Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, 2024).

Portugal confirmed the first circulation of the virus in July 2023, in the southern region of Alentejo (Oltretago), bordering the southern region of Spain, Andalusia and Extremadura. Subsequently, the viral circulation affected the whole country with a progressive increase in the number of diagnosed cases and of restricted areas. On 8 January 2024, the EHD outbreak notified in Portugal from the Direção-Geral da Alimentação e Veterinária are 349 (Direção-Geral da Alimentação e Veterinária, 2024).

In France, in September 2023, three outbreaks were confirmed in farms at the south-west border with Spain, on 18 January 2024, the number of confirmed outbreaks in the south-west region of France, were 3764 as reported by the Ministère De L'agriculture et De La Souveraineté Alimentaire (Ministère de l’agriculture et de la souveraineté alimentaire, 2024).

In Italy, the last outbreak in domestic animals, in particular bovine, was notified in March 2023, in Sardinia, in Sud Sardegna province, following a a positive PCR test, probably to be attributed to an infection contracted in the previous vector season. This outbreak was extinct on May 2023. In January 2024, in wild animals, one EHD outbreak was confirmed in Sardinia, in Cagliari province, following the positive result in one common fallow deer.

To January 2024 after the first incursion of the virus on the national territory, 12 outbreaks have been confirmed with overall number of cases as follows: 42 bovines, 67 ovine, 1 Sardinian deer and 2 common fallow deer. In Italy, the morbidity and lethality are 14.09% and 12.61%, respectively, but it is important to consider the presence of important variations in different farms.

In October 2023, Switzerland notified one EHD suspected case, following the detection of symptoms attributable to the infection in a calf, in the canton of Bern and in a cow on a farm in the canton of Jura. However, the subsequent analysis carried out by the reference laboratory of the World Organisation of Animal Health (WOAH) in France (ANSES, Maison-Alfort) on the blood sample taken from the two animals were negative, and the suspicion was lifted.

Regulatory updates

EHD is listed in Annex II of Regulation (EU) 2016/429 of the European Parliament and of the Council, known as 'Animal Health Law' (AHL), which means that it is subject to the rules on the prevention and control of the disease, which are enclosed in that body of legislation.

The disease was included, as it meets the requirements listed in Article 5 of the AHL, specifically all of the following criteria:- scientific evidence indicates that the disease is transmissible

- animal species are either susceptible to the disease or vectors and reservoirs thereof exist in the EU

- the disease causes negative effects on animal health or poses a risk to public health due to its zoonotic character

- diagnostic tools are available for the disease, and

- risk-mitigating measures and, where relevant, surveillance of the disease are effective and proportionate to the risks posed by the disease in the Union; and

- at least one of the criteria listed in Article 5, comma 3, letter b), specifically for EHD:

- the disease causes or could cause significant negative effects in the Union on animal health […]

- the disease causes or could cause a significant negative economic impact affecting agriculture [..] production in the Union

- the disease has or could have a significant negative impact on the environment, including biodiversity, of the Union.

Furthermore, according to the Commission Implementing Regulation (UE) 2018/1882 which defines the diseases listed in the AHL, the haemorrhagic epizootic disease of deer is referred to as D+E, this means that as:

- category D disease, measures are necessary to prevent its spread due to its entry into the Union or movements between Member States

- category E disease requires surveillance within the Union.

The rules related to these categories of diseases are listed in Article 9 of Regulation (EU) 429/2016 and, for EHD, concern the following susceptible families:

- Antilocapridae

- Bovidae

- Camelidae

- Cervidae

- Giraffidae

- Moschidae

- Tragulidae.

The vector species listed are Culicoides spp..

The Epizootic haemorrhagic disease is also a listed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) since May 2008 (WOAH, 2019) and the inclusion criteria are as follows:

- International spread of the pathogenic agent (via live animals or their products, vectors or fomites) has been proven, AND

- At least one country has demonstrated freedom or impending freedom from the disease, infection or infestation in populations of susceptible animals, AND

- Reliable means of detection and diagnosis exist and a precise case definition is available to clearly identify cases and allow them to be distinguished from other diseases, infections, OR

- The disease has been shown to have a significant impact on the health of domestic animals at the level of a country or a zone taking into account the occurrence and severity of the clinical signs, including direct production losses and mortality, OR

- The disease has been shown to, or scientific evidence indicates that it would, have a significant impact on the health of wildlife taking into account the occurrence and severity of the clinical signs, including direct economic losses and mortality, and any threat to the viability of a wildlife population.

Considering the epidemiological evolution of the disease, the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2515 amended the previous one. The Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/688 permitted only movement from the establishments situated out of an area of at least a 150 km of radius around the farm in which infection of epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus was reported in the previous 2 years prior to the departure. Currently, the new criteria introduced allow the movements considering the concepts of “seasonally disease-free area” and “vector protected establishment”, as for BT.

The current regulation lays down new conditions that make the movement of animals of susceptible species possible, even if they come from establishments within a radius of 150 km from farms where infected animals have been reported to have been kept in the previous two years, in fact they are granted in the case where:

- the animals come from protected establishments where they have been kept for at least 60 days, or 28 days with a negative serological test or 14 days with a favourable PCR result

- the animals come from territories considered seasonally free for at least 60 days, or 28 days with negative serological test or 14 days with favourable PCR result

- the competent authority of the Member State of destination, by way of derogation, may authorise movements that do not fulfil any of the requirements, after notifying the Commission and the other Member States.

References

- De Souza Santos, M. A., Gonzales, J. R., Swanenburg, M., Vidal, G., Evans, D., Horigan, V., Betts J., La Ragione R., Horton D., Dórea, F. (2023). Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD)–Systematic Literature Review report. EFSA Supporting Publications, 20(11), 8027E

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW). (2009). Scientific Opinion on Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease. EFSA Journal, 7(12), 1418

- Jiménez-Cabello, L., Utrilla-Trigo, S., Lorenzo, G., Ortego, J., & Calvo-Pinilla, E. (2023). Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus: Current Knowledge and Emerging Perspectives. Microorganisms, 11(5), 1339

- Kedmi, M., Van Straten, M., Ezra, E., Galon, N., & Klement, E. (2010). Assessment of the productivity effects associated with epizootic hemorrhagic disease in dairy herds. Journal of dairy science, 93(6), 2486-2495

- Lorusso, A., Cappai, S., Loi, F., Pinna, L., Ruiu, A., Puggioni, G., Guercio A., Purpari G., Vicari D., Sghaier S., Zientara S., Spedicato M., Hammami S., Hassine T. B., Portanti O., Breard E., Sailleu C., Ancora M., Di Sabatino D., Morelli D., Calistri P., Savini, G. (2023). Epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus serotype 8, italy, 2022. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 29(5), 1063

- Quaglia, M., Foxi, C., Satta, G., Puggioni, G., Bechere, R., De Ascentis, M., D’Alessio S. G., Spedicato M., Leone A., Pisciella M., Portanti O., Teodori L., Di Gialleonardo L., Cammà C., Savini G., Goffredo, M. (2023). Culicoides species responsible for the transmission of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease virus (EHDV) serotype 8 in Italy. Veterinaria Italiana, 59(1)

- Ministère de l’agriculture et de la souveraineté alimentaire (2024): https://agriculture.gouv.fr/mhe-la-maladie-hemorragique-epizootique

- Minsterio de agricultura, pesca y alimentacion (2024): https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ganaderia/temas/sanidad-animal-higiene-ganadera/sanidad-animal/enfermedades/hemorragica-epizootica/Enfermedad_hemorragica_epizootica.aspx

- Direção-Geral da Alimentação e Veterinária (2024): https://www.dgav.pt/animais/conteudo/animais-de-producao/bovinos/saude-animal-em-bovinos/doencas-dos-bovinos/doenca-hemorragica-epizootica-dhe/

- Regolamento (UE) 2016/429 del Parlamento Europeo e del Consiglio

- Regolamento Delegato (UE) 2023/2515 della Commissione

- Regolamento Delegato (UE) 2020/688 della Commissione

- Regolamento Di Esecuzione (UE) 2018/1882 Della Commissione

- Regolamento (UE) 2016/429 del Parlamento Europeo e del Consiglio

- Savini, G., Afonso, A., Mellor, P., Aradaib, I. A. O., Yadin, H., Sanaa, M., Wilson W., Monaco F., Domingo, M. (2011). Epizootic haemorragic disease. Research in veterinary science, 91(1), 1-17

- Sghaier, S., Sailleau, C., Marcacci, M., Thabet, S., Curini, V., Ben Hassine, T., Teodori L., Portanti O., Salah Hammami, Jurisic L., Spedicato M., Postic L., Gazani I., Osman R.B, Zientara S., Bréard E., Calistri P., Richt J. A., Holmes E.C, Savini G., Di Giallonardo F., Lorusso, A. (2022). Epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus serotype 8 in tunisia, 2021. Viruses, 15(1), 16

- Shope, R. E., MacNamara, L. G., Mangold, R. (1955). Report on the deer mortality, epizootic hemorrhagic disease of deer. NJ outdoors, 6, 17-21

- Spedicato, M., Profeta, F., Thabet, S., Teodori, L., Leone, A., Portanti, O., Pisciella, M., Bonfini, B., Pulsoni, S., Rosso, F., Rossi, E., Ripà, P., De Rosa, A., Ciarrocchi, E., Irelli, R., Cocco, A., Sailleu, C., Ferri, N., Di Febo, T., Vitour, D., Breard, E., Giansante, D., Sghaier, S., Ben Hassine, T., Zientara, S., Salini, R., Hammami, S., Savini, G., Lorusso, A. (2023).

Experimental infection of cattle, sheep, and goats with the newly emerged epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus serotype 8. Veterinaria Italiana

- World Organization for Animal Health, WOAH (2019) Epizootic haemorrhagic disease technical card: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/epizootic-heamorrhagic-disease.pdf

- World Organization for Animal Health, WOAH (2021) Terrestrial Manual, Chapter 3.1.7 Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease (Infection with Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus)

- Yadin, H., Brenner, J., Bumbrov, V., Oved, Z., Stram, Y., Klement, E., Perl S., Anthony S., Maan S., Batten C., Mertens, P. P. C. (2008). Epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus type 7 infection in cattle in Israel. The Veterinary Record, 162(2), 53.

Marta Cresci*, Massimo Spedicato, Valentina Zenobio

Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise “G. Caporale”

Centro Operativo Veterinario per l'Epidemiologia, Programmazione, Informazione e Analisi del Rischio

*Referente: m.cresci@izs.it