Recent and Re-emerging Lassa fever Outbreaks in Nigeria

Introduction

Historical perspective and Classification of Lassa fever virus

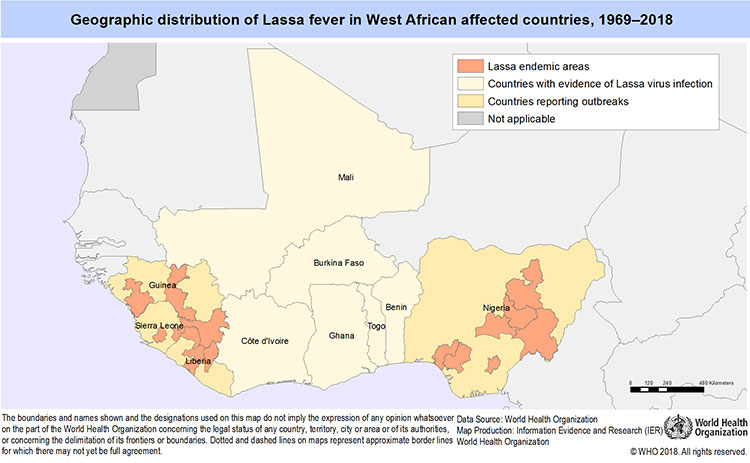

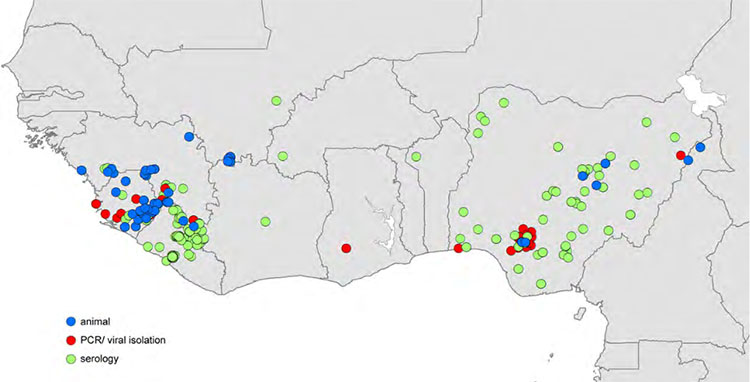

Lassa fever was first described in 1969 (Carey et al., 1972). The first case being an American missionary nurse (Ms Laura Wine) working in a village called Lassa, located in Borno state in north-eastern Nigeria. The patient who presented with symptoms of high fever, pharyngitis, myalgia and headache, later developed haemorrhagic manifestation and died within 30 hours of transfer to the nursing home in Jos (Frame et al., 1970). Three nurses in the hospital who looked after the patient contacted the disease and two of them died. The third nurse was evacuated to U.S where she recovered after a prolonged illness. Lassa virus was isolated at the Yale Arbovirus Research Unit (YARU) in vitro cell cultures inoculated with serum sample from all three patients (Buckley and Casals, 1970). Based on the morphological and serological similarities of the virus with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis (LCM), Machupo and Tacaribe viruses, the isolate were grouped together with these viruses in the Arenavirus genus as described by (Buckley and Casals, 1970). In keeping with the practices of arbovirology at that time, a geographic name was assigned to the disease and the virus, hence, the name Lassa fever and Lassa virus respectively, after the village where the index case was presumably infected. This was seen as stigmatizing by the Lassa community, especially considering the infectious nature of the disease (Frame, 1992a). Two persons working in a United State Laboratory with material from the original outbreak subsequently became infected, one fatally (MMWR, 1970; Leifer et al., 1970). A larger nosocomial outbreak, which occurred in Jos in 1970, with fatal results for the attending physician further increased the fear of Lassa disease (Leifer et al., 1970; Buckley and Casals, 1970). Work on live virus was suspended as Lassa fever disease assumed notoriety and was subsequently featured in New York Times. Lassa fever was first recognized in Nigeria in 1969, there were reports in 1950s of a disease with clinical presentation resembling Lassa disease in 1955 and 1956 (Rose, 1956 and 1957) epidemics reported from Sierra Leone clinically had strong resemblance to Lassa fever. Lassa virus neutralising antibodies had been detected in serum of a missionary nurse from Nigeria who recovered from a Lassa like illness in 1952 (Henderson et al., 1972). The nurse was found to have a major hearing defect in 1955, and serum sample collected from her in 1967 tested positive for Lassa fever virus. Sera from four other missionaries from Guinea, collected the same year, were also found to be positive for Lassa virus antibody and one of them had total nerve deafness which developed after a febrile illness (Henderson et al., 1972). The CDC laboratories also tested sera obtained from a WHO Trypanosomiasis survey conducted near the Benue River in 1965 and 1966, and more sera from the virus Research laboratory in Ibadan, collected between 1965 and 1970. About 9% of these sera were positive for Lassa virus neutralising antibodies (Frame, 1992b). It is probable that Lassa fever existed long before its first recognition in 1969, but did not have the high nosocomial transmission later observed in recent outbreaks. In March 1970, an outbreak was suspected in Zorzor, Liberia. A scenario similar to that of Nigeria occurred, the attending missionary nurse became infected and died (Mertens et al., 1973). Later, a number of the Lassa fever cases were confirmed serologically in the same year (1972); another outbreak of Lassa fever occurred in eastern Sierra Leone and was reported to the CDC. The CDC investigation yielded new and important insight of the disease (Fraser et al., 1974). Having placed Lassa virus in the Arenavirus family known to infect rodent, attempts were made to isolate the virus from small animals in Nigeria and Liberia (Wulf et al., 1975). However, in 1972, Lassa virus was isolated for the first time from tissues of Mastomys natalensis rodents, during the investigation of an epidemic in Sierra Leone (Monath et al., 1974b). Subsequent studies in northern Nigeria during an inter-epidemic period confirmed Mastomys as a reservoir host of Lassa virus (Carey et al., 1972). Further isolation of the virus was achieved from Mastomys, Rattus and Mus minutoides in Nigeria (Wulff et al., 1975). Since the year 1969 outbreak, several outbreaks of disease have been described with nosocomial spread of the disease in Nigeria and other West African countries notably Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea (White, 1972; Fraser et al., 1974; Bowen et al., 2000). It has been estimated that in West Africa as a whole there are 100,000 to 300,000 new cases (infections) of LF annually, with approximately 5,000 deaths (McCormick et al., 1987a&b). It has now been established that LF is known to be endemic in Benin, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Togo and Nigeria, and most likely exists in other West African countries (Mylne et al., 2015) (Figures 1a and 1b).

Figure 1a. Geographic distribution of Lassa virus in West African affected Countries, 1969-2018

Figure 1b. Reported locations of Lassa virus (LASV) infection used to build zoonotic niche maps. Blue circles indicate location mid-points for animal LASV infection surveys. Red circles indicate location mid-points where human cases of Lassa fever were diagnosed using PCR or viral isolation methods. Green circles indicate location mid-points where human cases of Lassa fever were diagnosed using serological methods. (Source: Mylne et al., 2015)

The phylogenetic analysis of full-length nucleoprotein, glycoproteins 1 and 2 gene sequences has suggested that the Nigerian strains of the virus are ancestral to Lassa virus (LASV) strains found in other West African countries such as Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone (Bowen et al., 2000). This could suggest that the virus most have been spread to these countries with the movement of the reservoir host (Mastomys sp.) to these West African countries. Certain factors among others could have been known to influence the emergence of LF and other haemorrhagic fever viruses in some geographic settings. These include: microbial evolution, environment e.g. climate change, social factors e.g. man-made armed conflicts, healthcare, food, behaviour and poor public health infrastructure.

LASV belongs to the Arenaviridae family. The name Arena, which means sand in Latin, was derived from the characteristics, sandy appearance of fine granules seen within virion in ultrathin electron microscopy (Rowe et al., 1970). Arenaviruses have been grouped on the basis of morphology, geography, and broad serological cross – reaction and to some extent on biologically specific cross neutralisation patterns (Murphy et al., 1969). The prototype of the family is the Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus (LCM), described in 1933 by Armstrong and Lillie (1934). The arenavirus family, Arenaviridae, is comprised of 1 genus, Arenavirus. Members of the genus Arenavirus, currently comprises of 22 recognized species (Salvato et al., 2012; Bukbuk and Baba, 2017). This genus is subdivided into two serotypes (complexes) based on serologic, genetic, and geographic relationships (Bowen et al., 1997; Charrel et al., 2008; Salvato et al., 2012). The two serologic groups of Arenaviruses are:

- LCMV-LASV complex (Old World-OW) Arenaviruses, are associated with rodents in the Murinae subfamily of the family Muridae.

- Tacaribe complex (New World-NW) Arenaviruses, arenaviruses are associated with rodents in the Sigmondontinae subfamily of the family Cricetidae. The NW group consists of 11 viruses; Junin, Machupo, Tacaribe, Amapari, Parana, Tamoani, Pichinde, Latino flexal, Guanorito and Sabia, Oliveros virus (Peters and Jahrling, 1994).

.

Figure 2a. Phylogenic relationships of Old World (OW) e.g. LUJV and New World (NW) e.g. TCRV viruses based on amino acid sequences of the nucleoproteins. (Source: Briese et al., 2009)

Figure 2b. Phylogenetic relationships of OW e.g. LASV and NW e.g. TCRV viruses based on amino acid segment sequence of the nucleoproteins. (Source: Ishii et al., 2009)

Lassa fever activity in Northeastern Nigeria

Although, the last outbreak of LF was first reported from Lassa town, Borno state in Northeastern Nigeria reports from the area have been scanty, until recently in March 2017 a period of almost five decades where a confirmed case was reported in a middle-aged woman (https://afro.who.int/news/borno-state-reports-first-lassa-fever-outbreak-48-years; https://ec.europa.eu/echo/field-blogs/stories/disease-surveillance-key-controlling-outbreak-lassa-nigeria_en). Previous serological studies on viral haemorrhagic fevers in Borno state, reported varying seroprevalence rates. After the discovery of Lassa virus in 1969, a serosurvey for LF activity conducted by Arnold and Gary in 1977 in rural Lassa community using neutralisation test reported an antibody prevalence rate of 5.8% among the subjects. In the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (UMTH), a tertiary health facility, Bajani et al. in 1997 reported a rate of 1.3% Lassa virus specific-IgG by Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Antibody (ELISA) assay in 3 out of 241 health workers. A more recent study however, showed a higher seroprevalence rate of 7.4% by IgG specific ELISA occurring in 22 out of 297 subjects tested (Bukbuk et al., 2014; Bukbuk and Baba, 2017).

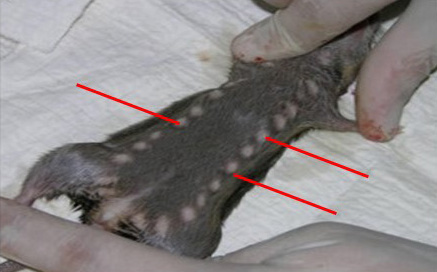

The peculiar geographical location of Borno State, which shares international borders with three other African countries (Cameroun, Chad and Niger), makes it vulnerable to cross-border spread of various diseases including Haemorrhagic fevers. Besides, the State has been reported as the niche of Lassa fever virus (LFV) (Bukbuk and Baba, 2017). The epidemiology and studies on the rodent reservoir host(s) of Lassa virus has not been adequately investigated in this ecological zone. Although the rodent, the multimammate mouse (Figure 3), Mastomys specie is the known reservoir host of the Lassa virus, the Mastomys natalensis species - complex still remains poorly defined (Granjon et al., 1997). Hence there is a great dearth of information on the role of different rodent species that are abundant in Borno state and other parts of Nigeria and the zoonotic spread of LF disease has not been adequately addressed.

Figura 3. Evidenziate le 12 paia di mammelle (frecce rosse) della specie Mastomys natalensis (Ref: Musser and Carlenton, 2005)

Re-emerging Lassa fever outbreaks in Nigeria

In this article, the authors would describe some outbreaks of LF in different parts of the country. Nigeria can now be said without equivocation or ambiguity to be hyperendemic for LF, as outbreaks have been reported from different parts of the Country affecting a large number of people in different geographical foci. LF cases has become more frequent within different communities and in health settings particularly among health workers, with cases spreading beyond its imagined known geographic boundary or niche. LF cases have been reported to be imported into other countries of the world from Nigeria (https://reliefweb.int/disaster/ep-2016-000141-nga). Since the first report of LF in Lassa village in 1969, several outbreaks were reported, with the year 2012 being the worst, when 623 cases with 70 deaths were reported from 19 (53%) out of the 36 states (Tambo et al., 2018). In the current outbreak as at Week 38 of 2018, cases were reported in twenty two states with 2,576 suspected cases out of which 510 were laboratory-confirmed positive, 10 probable (not a case), and 134 deaths with a case fatality rate in the confirmed cases of 26.3%. Twenty two states have recorded at least one confirmed case across 89 Local Government Areas (LGAs). From 1st

January to 25 March 2018, nineteen states have recorded at least one confirmed case across 56 LGAs (Edo, Ondo, Bauchi, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Anambra, Benue, Kogi, Imo, Plateau, Lagos, Taraba, Delta, Osun, Rivers, FCT, Gombe, Ekiti and Kaduna). In most of these reports, outbreaks and nosocomial transmission of LF among health care workers indicates that they have always been infected or are at a higher risk of infection. For example, as at week 38 of 2018, thirty-nine health care workers have been affected since the onset of the outbreak in seven states of Nigeria. Fourteen health care workers have been affected in six states (Benue, Ebonyi, Edo, Kogi, Nasarawa, and Ondo), with four deaths (case fatality rate= 29%). As of 18 February 2018, four out of the 14 health care workers were confirmed positive for Lassa fever

(https://ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps). A total of 1.022 cases including 127 deaths were reported from week 49 of 2016 to week 51 of 2017 (WHO, 30 Mar 2018.).

Conclusions

Outbreaks of LF has continued unabated in Nigeria with almost all the 774 LGAs in the 36 States including Abuja, the FCT reporting at least one confirmed case since the first case of the disease was reported from the Lassa village in 1969. In recent times, there has been an upward trend in the reported incidence, prevalence and mortality rate due to LF and its increasing spread within and outside the country. Infection caused by LASV continue to pose a major public health problem of immense significance in Nigeria and worldwide. This is coupled with the potential for the use of haemorrhagic fever viruses, including LASV as biological weapons as emphasized in earlier studies (Borio et al., 2002; Bossi et al., 2004; www.uic.edu./classes/dme/…/vhfpub.ppt) it also continues to be of great public health concern (Bukbuk et al., 2014). Currently, there are good, sensitive, and specific laboratory diagnosis for LF, reliable supportive treatment but up to now, no licenced LF vaccine has been developed by scientists yet. Hence, public health enlightenment on preventive measures against infection with the LASV is highly needed.

References

- Armstrong C., and Lillie R.D. (1934). Experimental lymphocytic choriomeningitis of monkeys and mice produced by a virus encountered in studies of the 1933 St. Louis encephalitis epidemic. Public Health Report, 49: 1019 – 1027.

- Arnold, R. B., and Gary, G. W. (1977). A neutralization test survey for Lassa fever activity in Lassa, Nigeria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 71(2):152 – 154

- Bajani M.D, Tomori O, Rollin P.E, Harry T.O, and Bukbuk N.D, et al. (1997). A survey for antibodies to Lassa virus among health workers in Nigeria.Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 91: 379–381

- Borio, L., Inglesby, T., Peters, C.J., Schmaljohn, A.L., Hughes, J.M., Jahrling, P.B., Ksiazek, T., Johnson, K.M., and Meyerhoff, A. et al. (2002). Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses as Biological Weapons: Medical and Public Health Management. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(18):2391-2405 (doi:10.1001/jama.287.18.2391).

- Bossi P, Tegnell A, Baka A, Van Loock F, Hendricks J, Werner A Maidhof H, and Gouvras G. (2004). Task force on Biological and Chemical Agent. Threats, Public Health Directorate, European commission, Lux embourg. Bichart guidelines for the clinical management of haemorrhagic fever viruses and bioterrorism related haemorrhagic fever viruses. EuroSurveillance, 9(12): E11- E12 [PubMed: 15677844]

- Bowen, M. D., Peters, C. J., and Nichol, S. T. (1997). Phylogenetic analysis of the Arenaviridae: patterns of virus evolution and evidence for cospeciation between arenaviruses and their rodent hosts. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 8:301–316.

- Bowen, M.D., Rollin, P.E., Ksiazek, T.G., Hustad, H.L., Bausch, D.G., Demby, A.H. (2000). Genetic diversity among Lassa virus strains. Journal of Virology. 74(15):6992-7004

- Briese, T., Paweska J.T., McMullan, L.K., Hutchison, S.K., and Street, C., et al. (2009). Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new haemorrhagic fever-associated Arenavirus from Southern Africa. PLOS Pathogens, 5(5):e1000455. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455

- Bukbuk, D.N., Fukushi, S., Tani, H., Yoshikawa, T., Taniguchi, S., Iha, K., Fukuma, A., Shimojima, M., Morikawa, S., Saijo, M., Kasolo, F., and Baba, S.S. (2014). Development and validation of serological assays for viral hemorrhagic fevers and determination of the prevalence of Rift Valley fever in Borno State, Nigeria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 108 (12):768 – 773. doi:10.1093/trstmh/tru163. Advance Access published October 24, 2014

- Bukbuk, D.N. and Baba S.S. (2017).The Resurgence of African Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers (AVHFs) in Nigeria. Virol. Immunol. J. 2017, 1(5): 000130.

- Carey, D. E., Kemp, G. E., White, H. A., Pinneo, L., Addy, R. F., Fom, A. L and Stroh, G. (1972). Lassa fever: Epidemiological aspect of the 1970 epidemic Jos, Nigeria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 66: 402 – 408

- Charrel R. N., de Lamballerie X., and Emonet S. (2008). Phylogeny of the genus Arenavirus. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 11:362–368

- Frame J.D. (1992a). The story of Lassa fever. Part I. Discovering the virus. New York State Journal of Medicine, 92(5): 199 – 202

- Frame J.D. (1992b). The story of Lassa fever. Part II. Learning more about the disease. New York State Journal of Medicine, 92(6): 264 – 267

- Frame, J. D., Baldwin J. M., Gocke, D. J, and Troup. J. M. (1970). Fever, a new virus disease from West Africa. 1. Clinical description and pathological findings. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 19:670-676.

- Fraser D.W., Campbell C. C., Monath T. P., Goff P. A. and Gregg M. B. (1974). Lassa fever in the Eastern province of Sierra Leone, 1970 - 1972. 1. Epidemiologic studies. Amercian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 23: 1131 – 1139

- Granjon, L., J.-M. DuPlantier, J. Catalan, and J. Britton-Davidian. 1997. Systematics of the genus Mastomys (Thomas, 1915) (Rodentia: Muridae). Belg. J. Zool. 127:7–18

- Lisieux, T., Combira, M., Nassar, E.S., Burattini, M.N., De Souza, L.T., Fereira, I., Rocco, I. M., Da Rossa, A.P., Vasconcelos, P.F., and Pinhdero, F.P. (1994). New arenavirus isolated in Brazil. Lancet, 343 (8894): 391-392

- McCormick, J.B., Webb P. A., Krebs, J. W., J. W., Johnson, K. M. and Smith E. S. (1987a). A prospective study of the epidemiology and ecology of Lassa fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 155:437-444. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71726-0_3.

- McCormick, J. B., King, I. J., Webb, P. A., Johnson, K. M., O’Sullvian, R., Smith, E. S., Trippel, S. and Tong, T. C. (1987b). Lassa fever: A case-control study of clinical diagnosis and course of Lassa fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 155: 445 – 455

- Mertens, P. E., Patton, R., Baun, J. J., and Monath, T. P. (1973). Clinical presentation of Lassa fever cases during the hospital epidemic in Zorzor, Liberia, March-April 1972. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 22: 780 – 784

- Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) (1970); CDC 19(12): 123

- Murphy, F. A., Webb, P. A., Johnson, K. M and Whitefield, S. G. (1969). Morphological comparison of Machupo with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: basis for a new taxonomic group. Journal of Virology, 4: 535-541

- Murphy, F.A. Webb, P. A., Johnson, K. M. and Whitefield, S. G. (1970). Arenaviruses in Vero cells: Ultra studies. Journal of Virology, 6 (4): 507-518

- Murphy, F. A., Whitefield, S. G., Webb, P. A. and Johnson, K. M. (1973). Ultrastuctural studies of arenaviruses. In: Lehmann-Grube Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and other arenaviruses. Springer, Berlin. Pp. 273-285

- Mylne, A. Q. N., Pigottb, D. M., Longbottoma, J., Shearera, F., Dudab, K. A., Messinab, J. P., Weissb, D. J., Moyesa, C. L., Goldinga, Nick and Haya, S. I. (2015). Mapping the zoonotic niche of Lassa fever in Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, doi:10.1093/trstmh/trv047

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). Situation report week 38, 2018 Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria. 2018. http://www.ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps/. Accessed 28th Sep 2018

- Paweska, J.T., Sewlall, N.H., Ksaizek, T.G., Blumberg, L.H., Hale, M. J., and Lipikin, W. I., T. (2009). Nosocomial outbreak of novel Arenavirus infection, Southern Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 15; 1598 – 1602

- Peters, C. J., and Jahrling, P. B. (1994). Initial characterization and prevalence of Oliveros virus, a new world Arenavirus from Argentina. In: Mahy B.W.J., Kolakofsky D., eds. Frontiers in viral pathogenesis; 9th International Conference on Negative strand viruses, estril, Portugal

- Rose, J.R. (1956). A new clinical entity? Lancet, 2:197

- Rose, J.R. (1957). An outbreak of encephalomyelitis in Sierra Leone. Lancet, 2:914 -916

- Rowe, W. P., Murphy, F. A., Bergold, G. H., Cassals, J., Hotchin, J., Johnson, K. M., Lehmann-Grube, F., Mims, C. A., Traub, E, and Webb, P. A. (1970). Arenaviruses: proposed name for a newly defined virus group. Journal of Virology, 5: 651-652

- Salvato, M.S.; Clegg, J.C.S.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Charrel, R.N.; Gonzales, J.P.; Lukashevich, I.S.; Peters, C.J.; Rico-Hesse, R.; and Romanowski, V. (2012). Family Arenaviridae.in: Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; King, A. M. Q.; Adams, M. J.; Carstens, E. B.; Lefkowitz, E. F., Eds.; Academic Press: 2012; pp. 714-723

- Tambo, E., Adetunde, O.T., and Olalubi, O.A. (2018). Re-emerging Lassa fever outbreaks in Nigeria: Re-enforcing “One Health” community surveillance and emergency response practice. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 7:37

- White, H. A. (1972). Lassa fever: a study of 23 hospital cases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 66: 390-398

- Wulff, H., Fabiyi, A. and Monath, T. P. (1975). Recent isolation of Lassa virus from Nigerian rodents. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 52: 609-613.

-

public health enlightenment on preventive measures against infection with the LASV is highly needed.

Web References

- Armstrong C., and Lillie R.D. (1934). Experimental lymphocytic choriomeningitis of monkeys and mice produced by a virus encountered in studies of the 1933 St. Louis encephalitis epidemic. Public Health Report, 49: 1019 – 1027.

David Nadeba Bukbuk1

Jasini Athanda Musa2

1 Dipartimento di microbiologia, Università di Maiduguri

2 Dipartimento di microbiologia veterinaria, facoltà di medicina veterinaria, Università di Maiduguri